Only Project:

An Interview with Matt Longabucco

Chris Kerr

Hollywood is in the nature of things because it adds to that nature.

-- Parker Tyler, The Hollywood Hallucination

It's a dream come true of the movies that you watched all 120 films shown at the Pavilion Theater in Brooklyn in 2010 and wrote a prose poem about every last one. Let's start with some establishing shots for The Pavilion Project. Would you direct us from where you live into the theater and onto the page?

The beauty is that the theater's right in my neighborhood, on the southwest corner of Prospect Park. I could dash there from my place in five minutes, eight with a stop at the bodega. The theater sits next to an extremely evocative traffic circle (I like things that go round and round) called Bartel-Pritchard Square. It was named after two buddies from the area, both lost in World War I. Why is this circle called a Square?--no one seems to know. There's a subway entrance across the street, so it's easy for friends to meet you while you stand under the big marquee and gaze at the glowing (because backlit) posters of the week's offerings. If friends show up early, there's a great bar a block away. Impaired or not, I took copious notes during the films. I started off the year using a fancy pen I'd tracked down, with a twisty flashlight on one end. It was too distracting, though, so I wound up writing notes in the dark on loose paper, and when I felt I'd probably filled up one quadrant of a page, I'd move to the next region. I came to like the jumble this process produced--deciphering my impressions later on helped me to shape the poems.

To find The Pavilion Project online is pretty easy (pavilionproject.blogspot.com), but be advised, there is another Pavilion Project: "The Pavilion Project is a campaign to raise $350,000 to Build the Right Place for Denver's Kids to Heal at the new Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Unit at Denver Health." Um, mine is the one about the movies.

Where do you like to sit?

The year of this project, 2010, turned out to be the year of 3D, which meant seats in the middle and rear of the theater were at a premium. I loved how theaters everywhere just pretended this wasn't going to be an issue. But a much bigger problem, as anyone who's visited the Pavilion can tell you, is the astonishing number of broken, missing, shredded, and stained seats. Others had been destroyed by a leak in one of the theaters and spent the year under a plastic tarp. Meanwhile, extremely tough-looking guys bring their girlfriends to deserted weeknight screenings and sit in the back making or eliciting strange, animalistic noises, so I'd find the farthest seat away even if that meant craning my neck from the front row. The same applied for groups of squealing kids and teenagers talking on their phones. Basically, situating oneself at the Pavilion is less about preference than dire necessity.

Why did you need or prefer to "do something weird for a year," as you kid in your piece about Eat Pray Love? Like you ask in MORNING GLORY, what the hell were you doing with your life?

One fateful day in 2009, my wife Carley and I were sharing writing fantasies, and I told her I'd thought that if we ever moved to a small town in middle America I'd like to spend a year seeing every movie at the local multiplex and write a poem at each one. The idea may have had its germ in Joe Wenderoth's Letters to Wendy's, which is so important to me in its hilarious, haunting, highly articulate relation to an ordinary but psychically immense cultural phenomenon. To my surprise, and because she's amazing, Carley told me not to wait but to try the project right away, in Brooklyn, and I did. The pieces wound up being less the tangentially-related poems I'd first imagined and more engaged with the movies themselves. And though I'd planned a book (I'd still like it to be one), friends urged me to start posting the poems, as I was writing them, on a blog. It was when I created the blog that I started using the word "project." The word had a funny association for me, at the time, in that my good friend and great poet Dorothea Lasky had just published a manifesto of sorts, entitled Poetry is Not a Project, in which she deplores a recent emphasis on elaborating constraints and concerns instead of attending to the work of poetry itself. I totally hear her, but for me constraints proved productive and engaging, and the blog raised the stakes in terms of forcing me to craft my responses quickly for a public forum.

When Eat Pray Love came out, I realized that the conceit of the book on which that movie is based was similar to my own, and I started paying attention to all those do-something-for-a-year gimmicks that suddenly seemed to be everywhere. But then later in the year, I was teaching Walden and I understood that this phenomenon has actually been around a long time, and one could argue that it occupies a deep seat in American consciousness. America itself is a project--explicitly so. The language of giving-it-a-whirl permeates our foundational texts.

Which one film is most emblematic of what you were consistently attentive to in writing about them all?

On its nine screens the theater ran about half of all the films distributed in the U.S. in 2010. It wasn't hard to love them all. I liked that it was impossible to predict how any given film might translate into writing. In terms of my thinking, it turned out that the very first film I saw in the whole project, Avatar, both colored and anticipated a lot of what followed, for a couple of reasons. First, because of all the 3D, I found myself writing a lot, all year long, about virtuality, both as a concern of film in our immersive age (it started to seem like every film was implicitly about the explosion of informational media/the internet/cyberspace) and about my experience as a consumer of media as a way of life. That was my avatar sitting in there. Second, there's a lot of heavy ideology in the film. It's apocalyptic (as many 2010 films turned out to be) and concerned with big themes of nature, humanity, technology, and otherness. All year I was struck, perhaps naively, by the extent to which stories--especially the kinds of stories that find their way into Hollywood films--are endlessly, profoundly centered on fathers and sons, families as a foundational unit, nations struggling with one another, the small- and/or large-scale social fabric being ripped and repaired over the course of 100 minutes. As time went on, I both enjoyed the endless iterations of those archetypal narrative concerns but also sometimes resisted or subverted the constant affirmation of our most conventional values--with all the disturbing byproducts of xenophobia, misogyny, homophobia, and worship of money and power that they inevitably produce.

I love that you didn't find it hard to love them all, identifying not as a Sherlock Holmes critic but rather as "Watson, the man who watches his reason give way to love." What do you love about movies?

From the moment I began to conceive of the project, I recognized how easy it would be to just poke fun at these films, some of which, let's face it, may have been thoughtlessly or even cynically made. We're of course encouraged to consume these objects, but we're also invited to critique them, to rate them from 1-5, to post reviews of what we buy, to press the like button or not, to evaluate anything and everything and constantly express and refine our preferences within the narrow field of mainstream culture. It's exhausting to languish in this paddock of supposed choice, preening oneself in hollow empowerment. At the same time, because going to the movies in New York can be an expensive hassle, in recent years I'd been doing an absurd amount of research to ensure that I would only ever see a movie I knew I would love in advance (and hence, not seeing many at all). I wanted to avoid all of these pitfalls with the project. Because I do love the movies. I used to go to a movie or two a week, growing up, with my parents, and I just took them all in. I wasn't a creature of taste, yet, or a maestro of critical distance. Not that criticality is a bad thing, or that we shouldn't ever grow up in our enjoyments, but in doing so it's possible to lose a sense of the way culture at its best is really an opportunity to change and experience our consciousness. At the movies, we hear echoes of other movies, we improvise connections, we dream, we commune. If you look at it that way, what does it even mean to say a movie is good or bad? It only becomes meaningful to say that you either took the opportunity or didn't. Having decided to take it, and having offered up my own ability to respond in writing as my bond, I was rewarded in a way that critique can't match. Because no movie left me with nothing to say--on the contrary, every movie wanted to speak and speak.

What makes you love one movie more than another?

Are you trying to get me to admit that I'm a helpless sucker for movies about schizophrenic ballerinas? But I never denied it.

I also go in for schizoid ballet flicks, like Modern Times, and won't try to get you to sour your refreshing Farberesque resistance to evaluation. But you've studied poet-critics extensively, and Projector superimposes analytical and lyrical impulses. What is the value in combining critical and poetic perspectives?

They relieve each other, I think. Analysis relieves poetry of straining for effect. Poetry relieves analysis of belaboring its task--it skips over the boring parts. It's true that poet-critics have a special place for me, especially ones who skew a bit more poet: Eileen Myles has written some of the sharpest essays I've seen in years, and Wayne Koestenbaum's new The Anatomy of Harpo Marx is one of the most original books I've ever read about film. Dana Ward's essayistic poems or poetic essays engage with popular culture in ways that have helped me articulate my own ideas about what I want to appreciate in movies and music.

What do you no longer appreciate in your writing? In the movie version of The Pavilion Project, what would you like to be different?

In my writing, I see snark creeping in, despite my efforts to keep it out. If I was more rigorous, I'd revise to root it all out, but I see how those moments give pleasure--they give me pleasure--and at the end of the day I'm pleasure's slave. In the movie version of The Pavilion Project, I'd like to be played by Mark Ruffalo, with Al Pacino as Surly Usher #2.

Earlier you mentioned having gone to the movies once or twice a week with your parents, and you spent quite a bit of 2010 away from home to watch films. How else have movies interacted with family for you?

The project was both deeply social and deeply selfish. I rediscovered the charm of going to the movies with friends--I invited many people to go with me, many times. I love the togetherness of watching, which I don't consider any less intimate than talking. To get a crazy-busy friend in New York to sit still in your presence for a couple of hours feels like a real accomplishment. And then maybe even go to the bar afterwards and talk about the movie!

Still, my daughter was two that year, and 120 movies is a lot of hours. My wife got to go with me quite a bit, and I tried to go at times when my daughter was occupied or asleep, but frankly I had no call to do this. It was like sailing off on a whaler or something. Coming back not laden with goods and riches but reports of strange visions--madness...

What role does film play in your affective life? I know this is getting very personal, but the emotional reasons we watch movies also need critical care.

It's not too personal, it's at the heart of what I was exploring. What springs to mind is how soothing the movies are. I'm fascinated by the life of the eyes, the drama of "mere" looking. For my whole life, the official rhetoric has been a hysterical hand-wringing over the essential passivity of the movie or television viewer. But that ability to simply observe seems increasingly like a gift. As Geoffrey O'Brien writes, "For the moment, in the dark, you had no choice but to turn off the analysis machine and let things be." New media is agitating, spastic--the way I check my phone, a thousand times a day; it's unsettling and upsetting, the analysis machine going full-speed all the time. All through 2010 I couldn't shake the feeling that the movies were over, that the most central medium of my life so far had been profoundly displaced, just like that. It felt nostalgic, to watch that way--blissed out on a newly-old-fashioned narcotic.

In GOING THE DISTANCE, I appreciate your impatience with another app of the analysis machine, discourse about the limits of language--the unsayable-untranslatability-of-experience routine--and your response, "blah blah blah, some patriarchal hang-up about possession and I'm sorry, who cares, who worries about this?" Would you direct us to a point in your writing where you went the distance, where you think you really got something articulated?

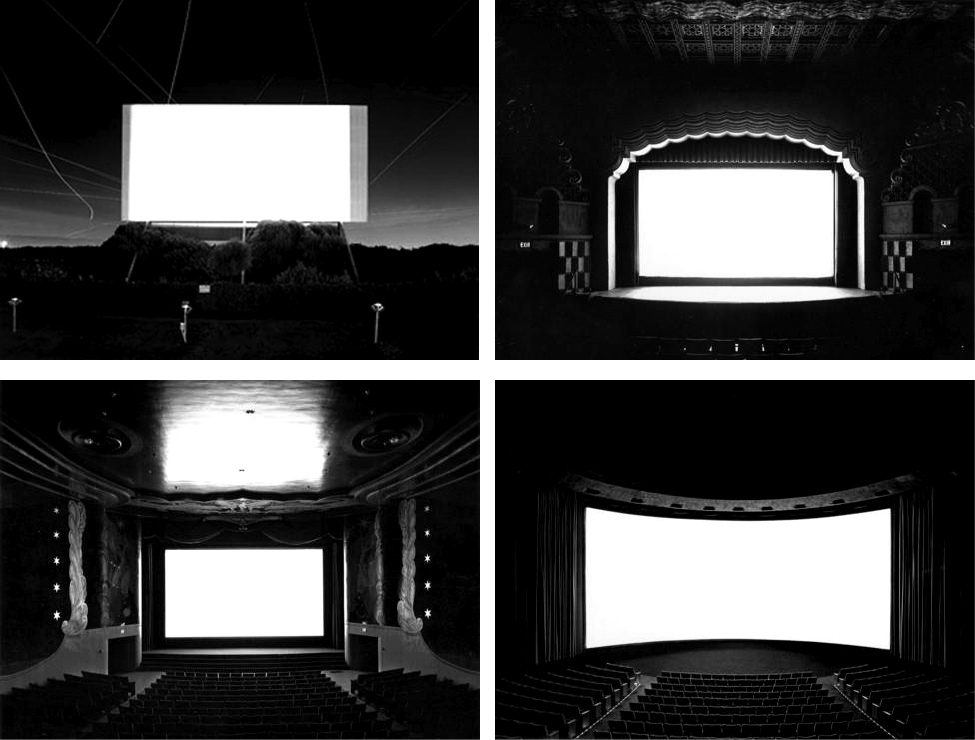

It really can get tiresome, echoing that insistence on the inadequacy of expression. I thank the movies for helping me announce even a momentary frustration with that position. After all, they have a special way of leveraging a total commitment to expression--in that hundreds of people labor for years on a Pixar film, and now it unfolds on a giant screen above you (or think of the way Hiroshi Sugimoto's theater photographs

argue for film as all-at-once, tending toward a perfect wholeness)--against an outrageous vulgarity, arbitrariness, hybridity, and contingency. They say both everything and nothing at once. In response to that, I felt liberated to try the same.

I leave it up to a reader to decide when I got it right. I sure had fun dissecting an orgasm in HARRY POTTER.

While reflecting on Up in the Air, you praise stepping "out the front door each day to be surprised by seeing or by knowing" and in TANGLED (3D) you suggest that the world itself can be surprised by us, that "impossibly, the world actively marvels at our rootless self-aware flesh." Do you believe the world in fact marvels at, for example, Gabriel Orozco seeing a photograph like Extension of Reflection?

I kept thinking of his picture as I read The Pavilion Project. Why do you write, in HOW DO YOU KNOW, that movies favor ontology over epistemology?

There's something dutiful and sterile about epistemology, whereas ontology is paradoxically light and animating. You don't get drunk and go to a psychic and ask, how do I know what I know? No--you ask: who am I, and what's going to happen next? Which are movie-questions, too.

And yet ontology's also a kind of bloodsport. Looking back at UP IN THE AIR, the question about seeing and knowing came after I saw two headless mannequins on the street that I didn't take for mannequins at first; and the claim about ontology in HOW DO YOU KNOW comes out of a sudden feeling I had that the movies want to co-opt us into their reality as badly as Jack Nicholson wants to take an ax to his family in The Shining (he comes through the door; movie-ness comes through the screen). If you're arguing about being, in a sense there's only room for one argument to prevail, since an argument about being can't, by definition, leave anything out, can't leave a space for another argument. Or if it can, hmmm, I like that idea....

The Orozco photograph is stunning. It seems infinitely productive of meanings and must be what he has in mind in his paragraph you sent me:

"Reality and realization: the maker [realista] who wishes for the accident. The object that arises in the world as a result of an unpredictable phenomenon and accident, but only when there is an act of consciousness--consciousness that is elicited by the reality of the body ready to receive it. The recipients: the surprise of the maker and the subsequent surprise of the realizer: he who activates the reality as a recipient of its future, he who realizes what is happening to him in the world. Acceptance of the real and its accidents. Acceptance of disappointment. Not expecting anything, not being spectators, but realizers of accidents, in which reality, when nothing is expected of it, gives us its gifts."

That's so fantastic. It makes me want to say, of course the world admires the photograph that frames the tire tracks that smear to join in a circle the puddles reflecting the trees. I mean, the world has got to be positively giddy not only to have created that image but to have had it registered so effectively as to produce a new thingness all its own.

While responding to Legendary you note, "The movies teach this: if you train blindfolded, when you later shed the blindfold you cannot fail," and in YOGI BEAR (3D) you remind us (through Alexander Kluge) that "out of every two hours we spend at the movies, we spend one hour in the dark." Do you think the physical cinematic apparatus--its dark flash between every bright frame--has an effect on viewers? For what might movie darkness train us? To what end do we wax on, wax off?

This question makes me think of Geoffrey O'Brien's The Phantom Empire, an astonishing book that claims that in our time the movies train us for everything we know and know how to know (so much for dispensing with epistemology). He writes beautifully about the special bafflement of going to the movies as a kid, trying to puzzle out this enormous, interlocking, century-in-the-making text with all of its endless, seemingly sui generis codes, tropes, and embellishments. That it's a waking dream would only seem to magnify its power. O'Brien would also remind us, however, that to train one's eyes to a dream means risking several kinds of blindness in the light of day. Once you've gotten to fly around the matrix, or be a blue superhero, are you really going to settle for your body, gravity, mortality, one thing after another instead of everything at once? Having gone into the theater, you may not want to go back out again. My solution, for that one great year, was not to bother to try.

| ← | 13 | → |